Program Case Study

Building a Volunteer Cadre for Native Seed Collection

Lessons from Heather McCargo, Founder of Wild Seed Project

By Tripti Thomas-Travers, October 2023.

Summary

All microhabitat programs must ensure that their participants have access to native plants, preferably of local genotype. But the availability of these plants, and the seeds to propagate them, may be very limited because the careful gathering, processing and propagation of local seed (and the distribution of the propagated plants) is not always commercially viable. Microhabitat programs may then undertake this work themselves, by engaging volunteers.

Village and Wilderness connected with Heather McCargo, the founder of Wild Seed Project, a noted seed stewardship and distribution organization, to gather her wisdom on fostering a volunteer cadre for seed work. What we learned is that seed work lends itself very well to volunteers, and that with thoughtful management (for which McCargo gave us some detailed tips below), a lot can be achieved with a relatively small number of reliable people.

Introduction

Access to native plants is foundational for successful microhabitat programs. Our exploratory research of programs reveals that such native plant availability is often made possible only by the intensive involvement of volunteers, who help collect, process and propagate native seeds for non-commercial entities, including sometimes, the microhabitat programs themselves. This is particularly the case in areas where seed of local genotype is not commercially available because the gathering and processing of ecotypic native seed is not commercially viable.

For this case study, we spoke with Heather McCargo, the founder and (recently-retired) former executive director of Wild Seed Project. We aimed to tap her wisdom on recruiting, training and sustaining an effective cadre of volunteers in native seed work.

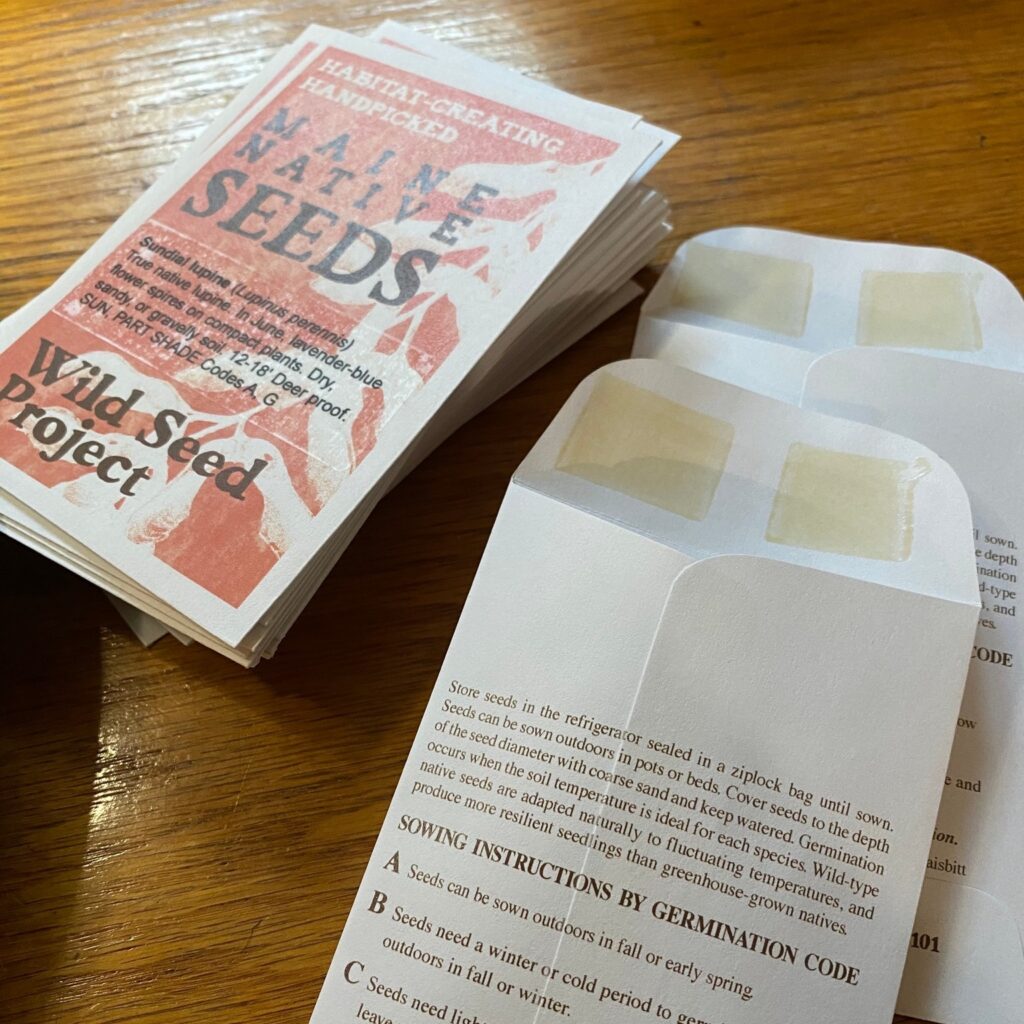

About Wild Seed Project

Wild Seed Project is a nonprofit based in South Yarmouth, Maine. Founded by McCargo in 2014, the organization is focused on putting responsibly-harvested native seeds and the knowledge of native plant cultivation into the hands of all. It aims to expand access beyond the traditional realm of experts and large-scale restoration work, so that anyone, at any scale, can participate in climate adaptation and the restoration of biodiversity.

Over the years, Wild Seed Project has developed many educational and applied-ecology offerings in addition to its seed stewardship work. It is, perhaps, most popularly known as a source of northeastern native seeds, which are sold via the Wild Seed Project (WSP) website. WSP also undertakes seed giveaways to teachers, schools, libraries, indigenous tribes and underserved populations. ”We really try to use the income from the seeds, as a non-profit, to make them available to all the different people who wouldn’t otherwise be able to access this natural resource,” says McCargo. The website features some 90 species of seed for sale every year, and in 2022 alone, the organization distributed and sold over 23,000 seed packets. Beyond its online inventory, WSP also serves as a source for hard-to-find seeds that may be needed for specialized projects. Enabling this work is a robust seed collection and processing program largely powered by a small group of volunteers who achieve impressive impact, given the quantity of seed that WSP (an organization of 10 staff members) is able to distribute.

Why Volunteers?

Our first question to McCargo was, why tap volunteers at all? Answered McCargo, “I knew from the start that the work of collecting, cleaning, harvesting and handling all the seeds was going to take a lot of hands. It is a huge amount of work. Just like the clearing of invasives, there is simply not enough time and money in the world to accomplish the task, especially as a small nonprofit. So I knew I would need volunteers.” And essentially, as McCargo, emphasizes, working with seeds is the perfect volunteer job: “The seed piece of the work is fun! It is really engaging work. I have people begging me to get involved in seed cleaning, sorting and packaging. And by getting them involved in this way, you can bring more people, not just professionals, into understanding more about native plants.”

When she first got started, McCargo recruited friends to join her around her kitchen table for what felt like a fun group project. That group has now grown to a long-term, core team of some 6-8 volunteers within a larger group of about 20 volunteers in total, with the original workers all handpicked by McCargo. Staff are trained and involved in the seed work as well.

We asked McCargo for some tips on creating a dedicated volunteer cadre for the task of seed collection, processing, sorting and packaging. The following is a cheat sheet, compiled from McCargo’s advice and observations:

Recruitment

- Not everyone is suited to seed work, so it is important to select volunteers carefully.

- Organize volunteer opportunities where people can first undertake more general tasks such as providing support at a booth or a presentation. This allows you to engage them in conversation and gauge interest, commitment, level of individual management that they might require, and skills such as manual dexterity.

- When interviewing candidates, keep the ball in your court by specifying that there are only a few openings for seed work. Volunteer prospects who are not ready or suited to this work can be deployed to other organizational tasks where they may be more helpful and effective.

- McCargo prefers seed volunteers who can be available once or twice a week, especially at busy times of year. Creating a regular schedule (same day and time each week) works well, but providing different options for days and times—such as weekends and evenings—also allows a wider range of people, including students and working adults, to participate. Be flexible for really good workers.

Training

- In-depth and repetitive training is crucial before a volunteer can be deployed. “The worst thing you can do is to have people going out and collecting wild seed and hurting the species, or collecting wild seed and wasting it because they collected it at the wrong time. It is a tricky process and we don’t want seeds being collected by people who don’t have use for it or don’t know enough to have a plan for how it needs to be collected, cleaned and stored. Some native plants, for example viburnum, cannot dry out after being harvested,” explains McCargo. She underscores that people have to learn a lot before moving up to specialized tasks, and seed collection, according to McCargo, is perhaps the most specialized of all.

- To become a collector of seed, McCargo feels strongly that you must understand the whole lifecycle of the plant, starting at the beginning: “If you are interested in seed collection, first you need to be a sower,” she states. She advises starting a new group of volunteers/trainees with winter sowing of up to a dozen species in December, so that in spring they can observe the plant germinating (WSP’s winter sowing guidelines can be found on its website in written form and as a video tutorial). Picking one species (or more, for more experienced volunteers) and following its lifecycle allows people to recognize the plant at all its stages of development and to recognize it in the wild, including when it is germinating, or not in bloom and inconspicuous.

- In spring, she also has new volunteers observe what is germinating in their own yards and in nearby public spaces, so they can get familiar with different emerging plants, the sources of seed and the concept of collection protocols on private, public or conservation land. (Detailed collection protocols developed by Wild Seed Project and the Maine Department of Transportation can be found in Chapter 3, page 153 of their joint publication “Maine Plants for Roadside Restoration.”) Then, volunteers pick one species to follow throughout the year.

- To get people finally started on collecting seed, it is important to choose the right seed, i.e. something that is easy to clean and locally abundant. For McCargo’s ecoregion, she recommends Little Bluestem, Schizachyrium scoparium, where running your hands gently up the stem releases the seeds that are ready to be harvested. Milkweed, Asclepias spp, is another option that is relatively easy, but can have its challenges, because harvesters need to learn to recognize when exactly a pod is ripe for harvesting the seed.

- McCargo typically runs an in-depth training program for volunteers and staff every two weeks from June to December. Training, again, is a repetitive task, and she has come to believe that people and plants are best served by people learning about seeds one or just a few species at a time.

Deployment

- When people gather for cleaning seed (or indeed for any volunteer task), be well prepared and have everything set-up before volunteers arrive.

- Keep volunteers and interns busy during their time on the job. Have lists of tasks that they can do in sequence, so they can easily move from one task to the next.

- Stay observant as a volunteer coordinator so you have the next seed trays available for cleaning, and can re-deploy or train people in real time.

- Have difficult-to-process seeds on hand so volunteers can tackle those tasks if they finish other tasks early. This also gives you a chance to observe persistence, disposition for repetitive tasks, and manual dexterity.

- Have a menu of other tasks—such as stuffing envelopes, sticking labels and stamps, etc.—for volunteers to tackle when they complete their seed work.

Community and Communication

- One of the most rewarding parts of seed work is being together as a group. Reinforce this community aspect by organizing periodic gatherings such as potlucks or annual celebrations, where volunteers can be thanked and recognized, and gifts—such as posters or other meaningful organizational swag—can be given as tokens of appreciation.

- Communicate regularly with volunteers to let them know of new opportunities, schedule changes, etc.

Conclusion

Overall, McCargo underlines how much volunteers enjoy contributing their time and effort to working with seed: ”Seeds are beautiful! Everyone likes working with seeds. It is joyful work! In fact, here at Wild Seed Project, we actually call it ‘seed therapy,’” she says. In her time building up Wild Seed Project, McCargo has taken a very hands-on approach to all the stages of creating a dedicated volunteer cadre. While this may not always be possible for large-scale operations, smaller organizations can learn valuable lessons about having outsize impact by thoughtfully managing even a small group of volunteers.

Village and Wilderness amplifies the work of community-based innovators by supporting efforts to discover, prove and share replicable climate adaption strategies. Our flagship project is the Microhabitat Program Incubator.

This case study is part of a series of written resource materials that Village and Wilderness is developing to share lessons and best-practices across existing and emerging microhabitat programs.

What is a Microhabitat Program?

Community-based programs designed to convert small patches of land into ecologically useful habitat are emerging everywhere. From rewilding private land, to establishing urban shade gardens, bioswales and pollinator-friendly roadside verges and farmland margins—restoring ecosystem function in the fragmented landscape is the common theme.

While “backyard habitat programs” is a term that has been commonly used to describe many of these efforts, we propose more encompassing terms—such as microhabitat programs. We believe that these programs are part of a broader movement comprising the universe of community-based and individual efforts and to restore ecosystem function and ecological productivity to the fragmented landscape.