Insights

Microhabitats as Plant Refugia

By Tom Chase, 10 April 2024

Several summers ago I was wandering around my yard’s own microhabitat on Martha’s Vineyard Island, when I came upon a small but strikingly beautiful flower that I’d never seen before. Usually when this happens it turns out to be some unfamiliar invasive species or an escapee from a neighbor’s garden. I was intrigued but skeptical. I’ve learned the hard way that waiting until I get around to properly identifying an unfamiliar plant can have consequences: procrastination leads to infestation. But something about this little beauty tugged at my botanically-hazy memory, so I pulled out my field-worn Newcomb’s Guide and keyed it out. It turned out to be Venus’s Looking-glass (Triodanis perfoliata). According to Swanson’s The Flora of Martha’s Vineyard, the last time it had been seen in my town was in 1893. The only other small population was on the other side of the island, if it still existed at all.

Where this plant came from is a mystery. Did it bank its seeds in the soil, just waiting for the microhabitat conditions? Did its nearly dust-sized seeds come on a migrating bird or the wind? I’ll never know, but the joy of discovery was soon replaced by a sense of responsibility. What if this was the last remnant of an island-adapted population? Even if that other population was still extant, it was far too distant for any pollinator to connect them. My plant was genetically isolated.

Genetic isolation can have multiple impacts, one of which is on local ecosystem function. Locally, Venus’s Looking-glass is like many of the Vineyard’s native species, with fewer than 10 populations (21%) or likely extirpated (15%). After generations of overgrazing, forest clearing, fire suppression and habitat destruction most of these species can no longer fulfill many important ecological functions, ranging from the specific (feeding fewer pollinators or serving as their host plants) to the general (less biodiversity, less ecosystem resilience). The irony is that few of these are “rare species”, in the sense of being Massachusetts- or Federally listed. They are regionally common, but locally rare and therefore no longer contributing to the local ecosystem.

Because of habitat fragmentation, many of the island’s more common plant species are also genetically isolated. That is, there are more populations but they are so distant and separated by roads and development that their pollinators cannot pass pollen from one population to another, nor can their seeds reach to colonize new habitats. Like Venus’s Looking-glass and other locally-rare species, many are doomed to decline over time, resulting in even more ecosystem dysfunction. They will likely be replaced by already common and abundant species capable of long-distance seed and pollen dispersal, resulting in a less biodiverse and resilient ecosystem.

Besides the impacts on ecosystem function, habitat fragmentation and resulting genetic isolation can lead to problems for the plant species themselves. For example, recent research by Acoca-Pidolle et al 2023 showed that habitat fragmentation led to pollinator declines, which caused a violet species (Viola arvensis) to increasingly self-fertilize by 27% over a mere three decades. The plant evolved flowers that were smaller and less conspicuous (presumably to pollinators as well). The implications are not only of inbreeding, but also accelerating a further decline in pollinators.

The impact of habitat fragmentation on floral isolation and ecosystem function is not unique to the Vineyard. It is probably happening everywhere that urban and agricultural growth divides up the land. And if there was ever an important role that microhabitats could play, certainly one of them would be to bridge populations of these vulnerable but not (yet) listed species. While including these species in microhabitats would help preserve the functionality of the local ecosystem, there may be an even greater role that they can play for climate adaptation. I’ll turn again to the Vineyard as an example.

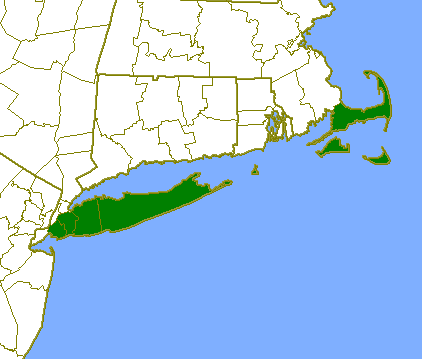

The Vineyard is part of the Sandplain archipelago, a chain of peninsulas and islands ranging from Long Island to Cape Cod known for its sandy, acidic, nutrient-poor, drought-prone, fire-dominated and salt-sprayed soil. Plants have adapted to this environment, so much so that some that looked quite different and were once thought to be restricted to the archipelago, turned out to be variants of more common and widespread species (Others indeed proved to be rare and regionally-restricted species.) Examples include species that might be expected to have long-range dispersal of seeds or pollen (e.g., shadbush, dwarf pitch pine, willow). I confess that at first, as a proudly parochial naturalist, I was a bit disappointed at their demotion. However, somewhat more important than my ego was the potential implications for climate change adaptation of the species. The genetic variation of the archipelago’s plants may be important to help these species adapt to harsher, drier conditions as climate changes.

Again, local adaptation is not unique to the Vineyard. Because it is an island, it is perhaps easier to conceptualize the impact of habitat fragmentation on genetic diversity and ecosystem function. However, probably most ecosystems exert influence on their local plants and the role the microhabitats can play on mitigating those impacts may be nearly universal. The question is, how do we insert them into our yards and neighborhoods, and which species are important?

Local botanists will be the best source for identifying which species would benefit from inclusion in microhabitats, but some broad parameters will narrow the list. First, unless specially-permitted, no State- or Federally-protected species should be planted on private microhabitats (and, especially, never should they be collected from the wild). Second, one can make an educated guess which common species need help by virtue of their restricted local distribution and by traits that suggest vulnerability to isolation, such as limited seed or pollen dispersal. Third, only those species that are likely to thrive in a given site should be recommended – and by “thrive” I mean not only planted where the ecological conditions of a given microhabitat are right, but also where they are apt to get the care they need. Fussy and sensitive plants need not apply where the landowner is not an attentive manager.

Counterintuitively, some native plants may thrive better in microhabitats than in the wild. My colleague Tim Boland noted that the Vineyard’s single native population of Turk’s cap lily (Lilium superbum) was one of them. The island, replete with well-fertilized landscaping and fragmented by roads and houses, near which hunters are not permitted to hunt, is a deer’s paradise. Now overabundant, the deer punish the wild population. Where are the lilies safe? In the most densely-developed parts of the island, which deer avoid. I suspect the same will be true of our once-abundant Wood Lily (Lilium philadelphicum). Both are stunning plants and neither are protected species (again, yet).

For field techs who make planting recommendations, a pragmatic concern will be availability of the species. Many nurseries operated by native plant societies carry a far greater variety of native plants than are advertised in commercial outfits. In other areas, it may be incumbent upon the microhabitat program to develop a list of priority species of seeds to be collected or plants to be grown in their own or a collaborating nursery.

For the landscape architect, another concern may be how showy and hardy a species is, especially when initiating the novice to microhabitats. Such “gateway” native plants are useful, but if used exclusively this can result in a narrow pallet of ubiquitous native plants, such as Echinacea and Monarda and Eutrochium. Often recommended as ideal plants for pollinators, the benefit is diminished if the pollinators are not pollinating those species that suffer from genetic isolation.

One expression I’ve heard is how to “sneak” some of these species in, as if there is danger that they will subtract from the beauty of the landscape plan. Personally, I’ve never seen an ugly plant species, but I accept that ugliness, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder. I have, however, seen some nondescript, isolation-prone species used in creative and attractive ways, such as a carpet of the tiny blue-eyed grass (Sisyrinchium spp.) bordering a pathway. A grassy-looking plant in the morning, it is a surprising spray of blue in the afternoon. A little creativity can make virtually any plant shine.

The folks at BiodiversityWorks’ Natural Neighbors program integrate ecologically vulnerable plants into landscapes in a more direct and assertive way: they simply include a few in the kits of plants they sell to their participants twice a year. They understand that these underrepresented plants do not need to be planted in great or conspicuous abundance. They often only need small populations widely distributed to keep the species genetically connected. Often they are merely part of the landscape’s texture and variety.

There is a natural tendency, I think, for many of us to envision our microhabitats as self-contained ecosystems, as small refuges in the midst of the fragmented landscape. But to be an antidote to that fragmentation, we need to envision our microhabitats as a mosaic, as a means to reconnect populations and to reintegrate biodiversity between wildlands. We need to think beyond the yard. Including more regionally-common-but-locally rare species will, I believe, help restore more resilient and functioning ecosystems.

Back to my Venus’s Looking-glass. I carefully collected the seeds from my lonely little plant and scattered them near the mother. A small cluster grew the next year. Later, as it happened, the observant and dedicated folks at Polly Hill Arboretum found a couple more hidden populations on the island. They collected seed, grew the plants, and have since offered them for sale. I bought a few plants myself, and am now more assured my little colony is less apt to be inbred. I suspect there are now dozens of populations spread in yards across the island. Some will survive, some won’t, but with luck whoever their pollinators are will find them, and new populations may spontaneously emerge elsewhere on their own. If so, their population and their ecological role, whatever it is, may be a bit more secure. That’s how nature works. People, too.